7 Layers of the OSI Model

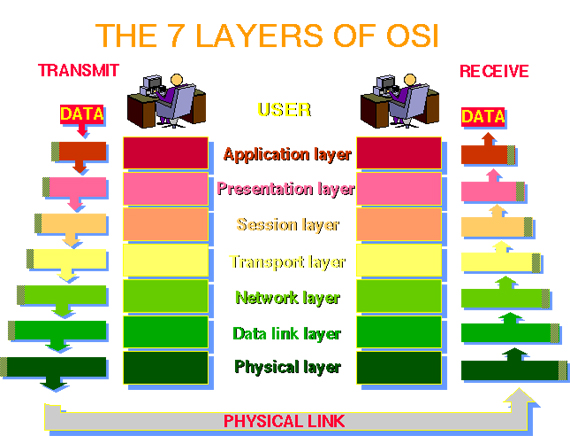

The OSI, or Open System Interconnection, model defines a networking framework for implementing protocols in seven layers. Control is passed from one layer to the next, starting at the application layer in one station, proceeding to the bottom layer, over the channel to the next station and back up the hierarchy.

|

|

The OSI Reference Model — Understanding Layers

It is time to take a trip up the OSI Reference Model, and learn what this mysterious thing is all about. The network stack is of great significance, but not so much that it's the first thing you should learn. Many so-called networking classes will start by teaching you to memorize the name of every layer and every protocol contained within this model. Don't do that. Do realize that layers 5 and 6 can be completely ignored, though.

The International Standards Organization (ISO) developed the OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model. It divides network communication into seven layers. Layers 1-4 are considered the lower layers, and mostly concern themselves with moving data around. Layers 5-7, the upper layers, contain application-level data. Networks operate on one basic principle: "pass it on." Each layer takes care of a very specific job, and then passes the data onto the next layer.

The physical layer, layer 1, is too often ignored in a classroom setting. It may seem simple, but there are aspects of the first layer that oftentimes demand significant attention. Layer one is simply wiring, fiber, network cards, and anything else that is used to make two network devices communicate. Even a carrier pigeon would be considered layer one gear (see RFC 1149). Network troubleshooting will often lead to a layer one issue. We can't forget the legendary story of CAT5 strung across the floor, and an office chair periodically rolling over it leading to spotty network connectivity. Sadly, this type of problem is quite common, and takes the longest to troubleshoot.

Layer two is Ethernet, among other protocols; we're keeping this simple, remember. The most important take-away from layer 2 is that you should understand what a bridge is. Switches, as they're called nowadays, are bridges. They all operate at layer 2, paying attention only to MAC addresses on Ethernet networks. If you're talking about MAC address, switches, or network cards and drivers, you're in the land of layer 2. Hubs live in layer 1 land, since they are simply electronic devices with zero layer 2 knowledge. Don't worry about the details for now, just know that layer 2 translates data frames into bits for layer 1 processing

If you're talking about an IP address, you're dealing with layer 3 and "packets" instead of layer 2's "frames." IP is part of layer 3, along with some routing protocols, and ARP (Address Resolution Protocol). Everything about routing is handled in layer 3. Addressing and routing is the main goal of this layer.

Layer 4, the transport layer, handles messaging. Layer 4 data units are also called packets, but when you're talking about specific protocols, like TCP, they're "segments" or "datagrams" in UDP. This layer is responsible for getting the entire message, so it must keep track of fragmentation, out-of-order packets, and other perils. Another way to think of layer 4 is that it provides end-to-end management of communication. Some protocols, like TCP, do a very good job of making sure the communication is reliable. Some don't really care if a few packets are lost--UDP is the prime example.

And arriving at layer 7, we wonder what happened to layer 5 and 6.

In short: They're useless.

A few applications and protocols live there, but for understanding networking issues talking about these provides zero benefit. Layer 7, our friend, is "everything." Dubbed the "Application Layer," layer 7 is application-specific. If your program needs a specific format for data, you invent some format that you expect the data to arrive in and you've just created a layer 7 protocol. SMTP, DNS and FTP are all layer 7 protocols

The most important thing to learn about the OSI model is what it really represents

Pretend you're an operating system on a network. Your network card, operating at layers 1 and 2, will notify you when there's data available. The driver handles the shedding of the layer 2 frame, which reveals a bright, shiny layer 3 packet inside (hopefully). You, as the operating system, will then call your routines for handling layer 3 data. If the data has been passed to you from below, you know that it's a packet destined for yourself, or it's a broadcast packet (unless you're also a router, but never mind that for now). If you decide to keep the packet, you will unwrap it, and reveal a layer 4 packet. If it's TCP, the TCP subsystem will be called to unwrap and pass the layer 7 data onto the application that's listening on the port it's destined for. That's all!

When it's time to respond to the other computer on the network, everything happens in reverse. The layer 7 application will ship its data onto the TCP people, who will stick additional headers onto the chunk of data. In this direction, the data gets larger with each progressive step. TCP hands a valid TCP segment onto IP, who give its packet to the Ethernet people, who will hand it off to the driver as a valid Ethernet frame. And then off it goes, across the network. Routers along the way will partially disassemble the packet to get at the layer 3 headers in order to determine where the packet should be shipped. If the destination is on the local Ethernet subnet, the OS will simply ARP for the computer instead of the router, and send it directly to the host.

Grossly simplified, sure; but if you can follow this progression and understand what's happening to every packet at each stage, you're just conquered a huge part of understanding networking. Everything gets horribly complex when you start talking about what each protocol actually does. If you are just beginning, please ignore all that stuff until you understand what the complex stuff is trying to accomplish. It makes for a much better learning endeavor